Recently, the term “POME” has generated considerable controversy, driven by misinformation and misunderstanding. This has resulted in widespread apprehension about its role in the EU biofuels sector. In particular, the plausibility of certified POME oil volumes and the biofuels produced from it is being called into question.

This article aims to shed light on the materials POME and POME oil, as well as the certification process under the ISCC EU scheme, and the plausible amount of POME oil generated.

What is POME, and how is it generated?

The word POME stands for palm oil mill effluent and refers to the voluminous wastewater emanating from the sterilisation and clarification process in milling oil palm fruits.

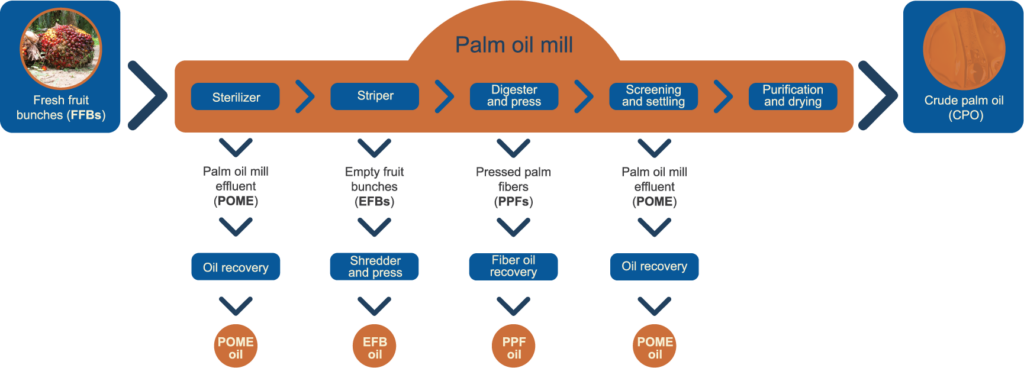

At a palm oil mill, harvested palm fresh fruit bunches (FFBs) are processed to obtain crude palm oil (CPO), which can be further refined into high-purity palm oil for food or other applications. The palm milling process (see Figure 1) involves several steps, such as sterilising palm fresh fruit bunches, stripping, digestion, and a combination of screening and settling. These steps generate various types of waste and residues, such as empty fruit bunches (after removing the oil-containing fruits), pressed palm fibres (after digestion and pressing of the fruits), and wastewater (POME).

POME is a brownish, viscous liquid with a strong odour and is about 90-95% water, with some amounts of residual oil, fatty acids, soil particles, and suspended solids. It has a high content of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids, and is quite acidic.

The wastewater is highly polluting and cannot be freely discharged into the waterways without going through, typically, an anaerobic and aerobic treatment. The anaerobic process breaks down the organic content, releasing methane, which can be (and is increasingly) captured and used to generate power, whilst the aerobic stage further oxidises the effluent, reducing pollutants before discharge. The aerobic treatment involves discharging the effluent into several open ponds. This ponding system, usually at the perimeter of the palm oil mill, consists of several connected “pools”. The open ponds enable the aerobic digestion of the organic content in POME, primarily to reduce its biological oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) before it is permitted to flow into waterways. A collateral outcome in these ponds is the separation of water and residual oil in the effluent, which floats to the surface. The desludging (skimming off) of this free-floating oil from the open ponds (sometimes necessary to ensure the anaerobic digestion of POME) constitutes one source of POME oil.

In addition, POME has several sustainable uses:

- Fertiliser (due to its nutrient content).

- Microbial biomass cultivation (for animal feed).

- Biogas (methane) can be captured from POME and used for power generation; each tonne of POME produces approximately 28 m³ of biogas[2]. Conservative estimates suggest this could support an annual power generation capacity of over 800 GW[3] in Indonesia and Malaysia.

- Recovery of residual oil in the effluent, e.g., as a feedstock for biofuel production.

POME as an “advanced” biofuel feedstock

Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) is classified as an “advanced” biofuel feedstock under the EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED), and this has sparked both interest and controversy. POME, alongside empty palm fruit bunches (EFBs) is included in Annex IX Part A of RED II, which lists specific types of waste and residue materials that are eligible for regulatory incentives to encourage their use in renewable energy production.

Particularly, the concept of “double counting” must be addressed here. When biofuels derived from Annex IX feedstocks are used in the transport sector, their energy content may be counted twice toward meeting national renewable energy targets. This is particularly relevant for the EU’s target of sourcing 29% of transport energy from renewables by 2030.

POME, like all other materials listed in Annex IX Part A, is considered “advanced” and is subject to mandatory minimum targets. These targets are designed to further encourage investments in technologies and infrastructure along the advanced biofuel supply chain. For example, the RED III introduced a combined minimum target of advanced biofuels and RFNBOs (Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin, i.e., derived from renewable electricity) of 5.5% fuel share in the transport sector in 2030, of which at least 1% must be RFNBOs.

At the same time, the RED demands a phasing out of biofuels associated with high land use changes, i.e. high indirect land use change (ILUC) risk, like palm oil from high ILUC-risk areas.

Finally, the use of waste and residue materials offers significant greenhouse gas (GHG) saving potential. These materials are regarded as having zero GHG emissions at their origin, which represents a considerable saving compared to any cultivated raw material, where emissions from cultivation must be taken into account.

Together, these drivers and incentives have contributed to the rapid growth in the trade and use of POME oil as a feedstock for advanced biofuel production.

Certification of POME oil under ISCC EU

The introduction of biofuels to the regulated European fuel market under the RED requires verification of the underlying supply chain through certification. This is especially important in the context of the targets and incentives mentioned earlier. Voluntary schemes recognised by the European Commission, such as the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC), offer a framework for companies and auditors to demonstrate compliance with the RED requirements, which is a precondition for entering the renewable transport fuel market under the RED.

ISCC anticipated the complications arising from the lack of clarity regarding POME oil and recognised the need for a clearer, more robust certification process. Therefore, ISCC initiated several working groups and stakeholder consultations with the following objectives:

- to address uncertainties regarding the definition of POME oil;

- to develop clear guidance for certifying individual palm oil mills;

- to assess the plausible volumes of POME oil that can be collected at mill level.

Although local experts with technical knowledge were involved, neither of the regulatory agencies from Indonesia nor Malaysia participated in these stakeholder dialogues, which has (and continues to have) made the subsequent local adoption of these definitions of POME and POME oil challenging.

Defining POME oil: from wastewater to feedstock

Before POME was listed in Annex IX of the RED II, there was some trade in waste oils from the palm oil milling process. These were traded under various terms such as palm oil slurry, palm oil sludge, oil palm slurry, oil palm sludge, decanter cake, but mainly as palm acid oil. The use of such differing nomenclatures was also to avoid restrictions on the import of waste materials into certain countries. These oils were mainly used for making hard soaps, low-level oleochemicals, grease and lubricants, and in animal feed.

Under ISCC EU, through the aforementioned working groups and stakeholder dialogues, a harmonised definition was developed where POME oil refers to the oil recovered from any wastewater from the palm oil mill. This includes the oil skimmed off the ponds, but also any oil recovered prior to the discharge into ponds, for example, via fat traps or centrifuge technology. Additionally, a considerable amount of wastewater is generated during the sterilisation process, where the fresh fruit bunches are sterilised by steam. Therefore, the definition of POME oil under ISCC EU is broader than simply the oil skimmed from wastewater in open ponds. This should be kept in mind when assessing POME oil potential.

ISCC EU has strict rules and disciplinary processes in place if the boundaries of the definition are exceeded. Labelling or selling other types of oil (e.g., Palm Fatty Acid Distillate – PFAD, or crude palm oil – CPO) as POME oil is a serious and fraudulent breach of ISCC EU requirements and results in consequences such as withdrawal of the certificate and exclusion from recertification.

Estimating plausible POME oil yields

ISCC EU has developed a guidance document for waste and residues originating from palm oil mills[1]. This guidance is an essential component for the mandatory auditor training and provides clear definitions of the respective waste and residue materials, explains their origin, describes the certification approach, and estimates how much of them can plausibly be assumed to be generated at the palm oil mill. Typically, the amount of POME oil generated correlates with the amount of palm fresh fruit bunches (FFB) processed. For POME oil, this mainly depends on the efficiency of the mill and the technology in place:

- Horizontal sterilisation: 2.1-7.6 kg/tonne FFB

- Vertical sterilisation: 6.0-28.8 kg/tonne FFB

It must be emphasised that these numbers serve as an assessment of an individual palm oil mill, where FFB processing capacity and the technology used in the mill, etc., are taken into account. In the case of a relatively inefficient oil mill using vertical sterilisation, where more oil is lost in the wastewater and may consequently be recovered as POME oil, up to 28.8 kg/tonne FFB could be considered plausible. However, the more efficient horizontal sterilisation is most commonly utilised[4]. According to industry experts, only about 10% of palm oil mills are using this technology. This distribution results in an average POME oil yield of up to almost 10 kg/tonne FFB.

Strengthening the certification process

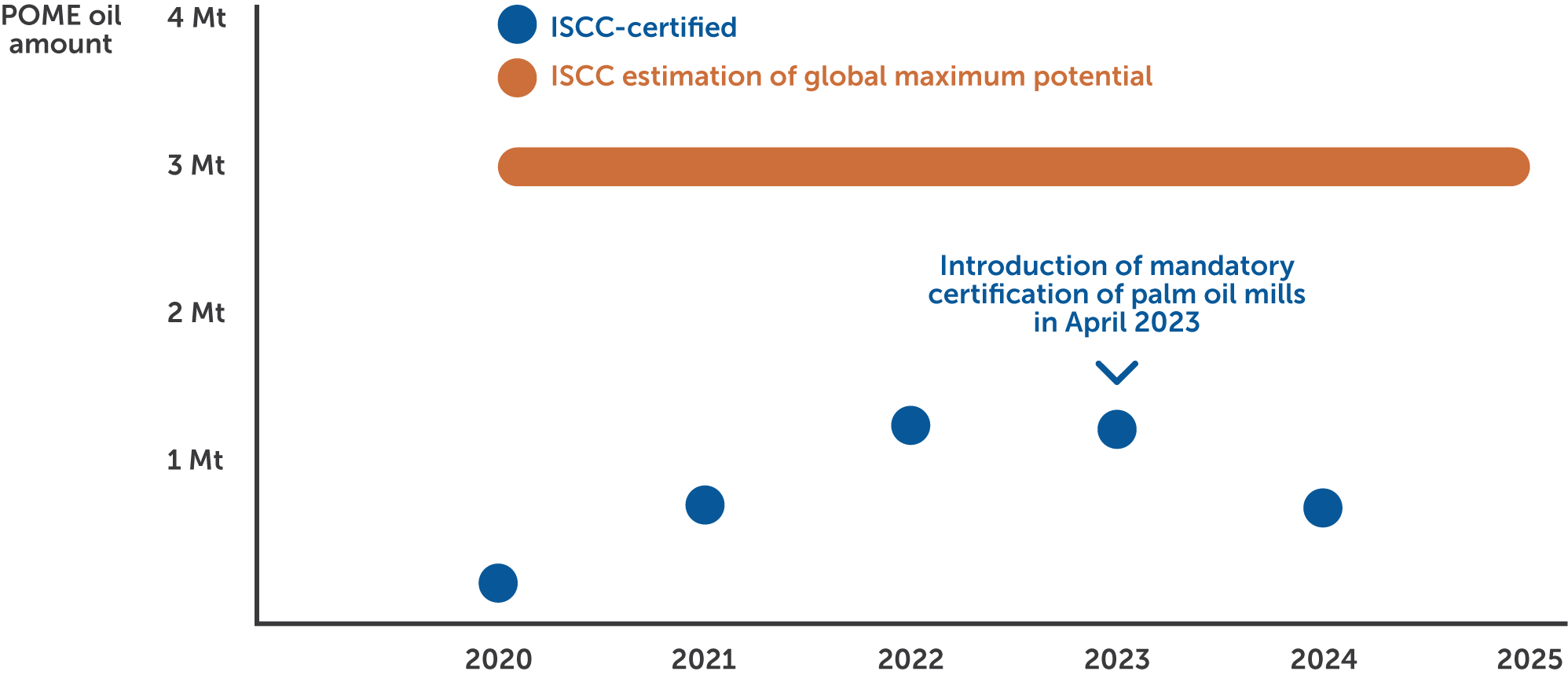

Waste and residue materials are typically collected from different waste-generating entities (so-called “Points of Origin”), with the collecting company being the first entity in the supply chain that needs to be certified and thus annually audited. In the case of palm-based wastes and residues, ISCC EU has made it mandatory for the Points of Origin, which are the palm oil mills, to be individually certified (effective from April 2023) to ensure stringency.

For these certifications of palm oil mills, ISCC EU has developed a questionnaire tailored for palm oil mill audits, where the auditor checks the annual amount of processed fresh fruit bunches, the mill’s sterilisation technology, the recovery method of POME oil, and the annual amounts of the generated waste streams. The auditor must assess the plausibility of the waste and residue amounts based on the yield ranges stated above, according to the ISCC EU guidance document.

A fragmented global understanding of POME oil

When assessing the potential of POME oil and its derived biofuels on a national or even global scale, this goes beyond the assessment of an individual oil mill as covered by the certification. Nevertheless, a standard definition of POME oil is necessary to link these two scales. The inclusion of the steriliser condensate in the definition of POME oil is not yet universally accepted. While the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) prohibited the recirculation of steriliser condensate oil into crude palm oil several years ago (which was a clear indication for it to be regarded as wastewater), they have recently required all types of oil produced from palm fruit milling, including steriliser condensate (and EFB oil), to be classified as crude palm oil. This directive might have been to collect statistics and taxes. ISCC EU sought clarification on this, but is still awaiting a response from the MPOB.

Estimating global POME oil potential

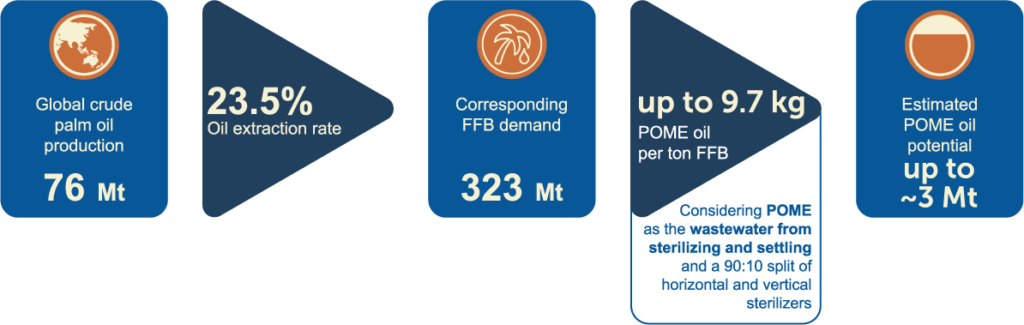

In April 2025, T&E published an article[5] claiming that the amount of POME oil-based biofuels in the European market in 2023, estimated to be about 2 million tonnes of POME oil, exceeds the global production capacity and therefore suggests fraud in the supply chain. Studio Gear Up[6] challenged this conclusion, which estimated the global capacity would be around the current consumption of 2 million tonnes. These estimates were based on typical POME wastewater amounts in crude palm oil production and the oil content of POME. It is unclear whether the above estimates include various sources of POME oil (i.e., from the steriliser condensate) as well as recovery prior to the pond system. Therefore, ISCC EU conducted an additional estimation based on the on-the-ground expertise and guidance, translating the global crude palm oil production (76 million tonnes[7]) into amounts of fresh fruit bunches (with 23.5 % as typical oil yield[8]) and using the 90:10 split of horizontal and vertical sterilisers as well as the above-mentioned POME oil ranges per technology. This approach results in a maximal global POME oil potential of up to approximately 3 million tonnes (see figure 2). The broad range thereby reflects the yield spread of individual mills.

Another approach can be based on research literature[2], [9] which reports that typically 5-7.5 metric tonnes (Mt) of wastewater are generated per Mt of crude palm oil, and 0.7 g of fat is contained in 100 g of POME (see table 1 in reference [2]). Given the global production of 76 Mt of CPO, which generates 380-570 Mt of POME with a fat content of 7 g/kg, a global POME oil potential of up to 4 Mt can be estimated.

However, one needs to consider that not all of that fat will be recovered, making this number rather a theoretical maximum.

Indonesia, as the largest producer of crude palm oil globally (47 million tonnes[7]), could, according to the ISCC EU estimation from above, generate up to almost 2 million tonnes of POME oil. However, an Indonesian estimation mentioned only 0.3 million tonnes[10] of palm waste products. As it is not clear which definition of POME (oil) is the basis for this estimation, we can only speculate that it may not include the steriliser condensate or generally POME oil recovered prior to discharging to the ponds. Applying the definition of POME oil and the different approaches to estimate global POME oil potentials as elaborated above, the estimation of only 0.3 million tonnes of POME oil generated in Indonesia is well below realistic POME oil numbers. Such contradictory estimations emphasise the importance of clear definitions and a common understanding of POME oil.

A final aspect to mention when discussing any oil (be it CPO or waste oils) originating from Indonesian palm oil mills is export duty evasion. Labelling CPO as various derivatives of palm oil as a means to evade export duties has long been a feature of the exports of palm products, especially where differential export tariffs favour some palm products while subjecting others to very high export duties. This is another reason for a higher risk associated with the palm supply chains. ISCC, with its rigorous individual certification of each palm oil mill, aims to mitigate this risk. This level of scrutiny is specifically designed to detect irregularities and prevent fraudulent declarations.

A decline in ISCC EU-certified POME oil volumes

The introduction of mandatory individual certification for palm oil mills supplying waste and residue materials has made it more difficult, especially for smaller mills, to participate in the certification system due to the effort and costs involved. As a result, some mills may have opted out, which, most likely, combined with an increased stringency in certification, has contributed to a decline in ISCC EU-certified volumes of POME oil (see Figure 3).

While discussions about the plausibility of reported volumes continue, it is important to recognise that ISCC-certified volumes represent only a part of the global potential. Many palm oil mills worldwide are not certified under ISCC EU, and this should be taken into account when interpreting certified quantities in a global context.

Conclusion: Towards clarity and confidence in POME oil

The lack of a common understanding of what POME oil is, its certification process, and the plausible volumes is causing misunderstandings and uncertainties. Clear definitions, as developed by ISCC EU, are essential to a) establish the basis for estimating national or even global POME oil potentials and b) enable target setting and certification for the European biofuel market. Recent discussions reveal the absence of such a shared understanding of POME oil generation.

ISCC EU has been addressing the uncertainties surrounding POME and POME oil by introducing a definition to harmonise terminology and understanding. To prevent fraud, ISCC EU has been strengthening the certification process for waste and residues from palm oil mills. ISCC EU is committed to further enhancing its certification process with stakeholders and following the requirements set by the European Commission and EU Member States.

To conclude, ISCC EU aims for a constructive exchange to establish a common understanding of POME oil, eliminate uncertainties related to this material, and harness its potential to support a transition towards a more sustainable economy – for which the utilisation of waste and residual materials like POME oil is one essential step.

Sources

- ISCC EU Guidance document: Waste and Residues from Palm Oil Mills (v3.1); developed with a working group of stakeholders and industry experts.

- Aziz et al. Acta sci. Malays. 1.2 (2017), 9-11.

- Bioenergy Consult (2024) Properties and Uses of POME.

- Thang et al., Pertanika J. Sci. & Technol. 29.4 (2021), 2705 – 2722.

- T&E (2025). Palm oil in disguise? How recent import trends of palm residues raise concerns over a key feedstock for biofuels

- studio Gear Up (2025). Current POME-based biofuels in EU fall within current production potential.

- Statista

- Azis et al. J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 94.1 (2015), 143-150

- Mahmod et al. J. Water Process Eng 52 (2023) 103488.

- Global Agricultural Information Network (2025). Indonesia Curbing Palm Waste Exports – DiscouragingCPO Mixture Practices.